Anthro Majors Shine at 2015 Senior Convocation

Posted in Announcements Students | Tagged Convocation, Graduation, Student

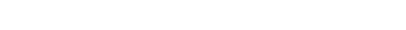

Georgetown’s 2015 Commencement Weekend began with Senior Convocation, which was highlighted by speeches from two members of the Class of 2015. Citlalli Alvarez and Alex O’Neill, both Anthropology majors, were selected from a class of more than 1,750 graduates and delivered thoughtful and passionate addresses to their classmates.

Citlalli urged the senior class to fight for justice and build bridges to help create a better world, while Alex reminded his classmates of the environmental challenges facing the planet, the choices that will have to be made, and how they will impact all inhabitants of the world.

The Department of Anthropology would like to thank Citlalli and Alex for all they have done to enrich our community and for inspiring us with their compassion and wisdom. We look forward to following their journeys beyond the hilltop!

CITLALLI ÁLVAREZ

Undoing the Borders to Global Citizenship

Georgetown will proudly tell you this is a global university that produces global citizens. In fact, if you search Georgetown’s website for the phrase “global citizen” you are prompted to 1640 results. Among those pages you’ll read that, “every citizen bears the responsibility to weigh the consequences of their actions for society’; that our education is meant to teach us how “Many of the discriminating power structures, injustices, and inequalities worldwide are bred and reproduced through a lack of awareness on how our lives are interconnected.”

These phrases remind us that as Georgetown graduates we are uniquely implicated by the call to global citizenship. To answer this call we must acknowledge and act upon our responsibility to humanity—to all humans.

Admittedly, when I first arrived at Georgetown it was difficult for me to think of myself as a “global citizen.” As an undocumented young Latina, I was well aware that citizenship is exclusive, that there are people within and outside of its protections and privileges. Yet, during my time here I developed an understanding of “global citizenship” as an identity that transcends borders, both literal and figurative, which helped me talk about and understand my own experience.

Perhaps most importantly, to become global citizens it is imperative that we critically assess what divide us and directly address the injustices that stem from these divisions.

One of the first books I picked up which truly breathed life into my soul is Gloria Alzandúa’s Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. In it she writes, “Borders are set up to define the places that are safe and unsafe, to distinguish us from them.” In this sense, borders are not simply national borders, but constructed social realities influenced by race, gender, class, ability, and sexuality: these borders that cloud our mutual humanity. My point here is that to become global citizens we must begin by undoing borders.

To understand exactly what I am referring to we need only to reflect on the past ten months in America. We cannot deny that our senior year has been a striking reminder of the lasting legacy of racial oppression in our country. The Georgetown bubble could not shield us from the historic events in Ferguson, New York, and now the ongoing protests not too far from our hilltop home in Baltimore. The country is shaken, and rightly so.

In these critical moments we feel the immense impact of the philosophy underlying global citizenship. Importantly, to stand on the side of justice we must build bridges.

This year, Georgetown has been a place to engage in constructive dialogue, as well as a place to express our deepest frustrations. In the weeks following the tragic shooting of Michael Brown, President DeGioia reminded our university community that “In moments of national turmoil, universities are a unique place to reflect, to convene discussions, and to engage in dialogue about the many aspects of the events unfolding around us. Being in a university community allows us the opportunity to learn from one another, and to reach a deeper understanding of the implications of events occurring at this moment in history.”

This year alone, with the leadership of our seniors, Georgetown students have successfully organized for fair wages, a diversity requirement, and a place to call mi casa (my home). Students have “died-in” for Black lives, and celebrated our LGBTQ community when faced with the presence of a hate group on our campus. And these are just a few things. We have done much more.

Yet, although I would love to continue to praise this senior class for their amazing accomplishments, and of course, for making our campus a better home for future Hoyas, I must point out the vast majority of us will leave the hilltop behind. However, we cannot leave behind this spirit of inclusivity, of justice. This is, after all, what we were meant to inherit from Georgetown.

Undoubtedly, this class of Hoyas will go on to change the world of policy, of business, of medicine, of the arts. We will be key stakeholders in conversations that will shape the future of our world. Wherever we go we carry the responsibility of global citizenship.

Our Georgetown education has given us a critical knowledge base from which to explore the needs and demands of humanity. Knowledge transcends borders, and it is on us to engage ideas from the pages of Charles Dickens to Maya Angelou. As Georgetown graduates, we take on take on a unique responsibility to rebuild a more just commonweal, and more just world.

To close, I return to Alzandúa, and leave you this quote: “Caminante, no hay puentes, se hace puentes al andar.” (Voyager, there are no bridges, one builds them as one walks.) Go forth. Build bridges.

ALEX O’NEILL

When John Carroll purchased our Hilltop about 225 years ago, it was a very different place. Instead of that ceiling up there, imagine a dense canopy of elms, oaks, and hickories. Instead of the (imported) pecan-wood floor under your feet, you’d feel humic soil, and you’d smell pungent, interwoven networks of fungal mycelia, wild onion, and fragrant elderberries.

Since that time, Georgetown has chosen to replace most of this natural charm with a more constructed vision of beauty: the iconic Healy Hall, Regents, and The Healy Family Student Center. (Even a Zoo, called New South!). But in the process of developing and expanding, we’ve compromised our natural history.

Of course, we lose ideas, constructs, species, and genetic information all the time. Change is a natural part of the world order – much of it is dictated by chance and gradual shifts that are completely out of our control. But every so often – especially now amidst human-aggravated, environmental change—we need to ask ourselves: what are we willing to compromise to foster development? What do we want to leave as a legacy “for generations to come?” And, perhaps most important, what species do we choose to save?

At this point in earlier drafts of this speech, I planned to talk to you about my experiences on a very different Hilltop, high in the Nepali Himalayas. I was going to enlighten you about plants, and tell you about how I told my parents, “Listen, I’m going to postpone my senior year to study drugs in South Asia.” (You’ll just have to imagine their horror!). I had planned to detail for you my adventures with shamans in villages perched 15000 feet in the sky, who treat their ailing residents with caterpillars parasitized by a zombifying fungus.

But then an immediate, acute environmental change struck. A type of change so outside my frame of reference that I have been forced to reconsider my past and future work in South Asia—and to rewrite this speech.

Sixteen days ago, on 28 April, the largest earthquake in recent Himalayan history ravaged central Nepal. The death toll has since climbed above 7000. (There is) immeasurable suffering, loss of history, architecture, and culture. Looking at pictures sent by my Nepali friends, I see three ancient kingdoms of the Kathmandu Valley leveled. Instead of fog, the smoke from funeral pyres blankets what many of us imagine as the Valley of Shangri-La. And we cannot even begin to describe the loss and devastation in areas outside of Everest and Kathmandu Valley, where damage has yet to be surveyed.

Picture the Capitol and the White House, the monuments on the Mall, the masterpieces in the National Gallery, the blooming cherry trees, and the entire tidal basin, now only rubble. That’s what’s happened to Nepal.

The earthquake shook my environmentalist and conservation-minded conception of human life, culture, and biodiversity to another level. I felt the suffering of my friends and a country I have come to love. The earthquake decimated villages where I had lived and worked for a year. It led to the death of Jang Bahadur, one of the shamans with whom I collaborated. And it left countless friends as well as their relatives without homes, water, or medicine.

Over the past few years, we’ve seen events like this in Japan and in Haiti, and as the Provost just mentioned, hurricanes closer to home. And we have learned that no situation, even on a scale like this earthquake, is simply someone else’s problem. Service is at the very core of our Georgetown identities. We are men and women—no, a spectrum of identities—for others. And we are resilient people.

The earthquake is a pressing catastrophe that calls us to immediate action. And although we’ve become acclimated to the heights of our Hilltop, we know that the world contains a range of summits to crest. Each of us—whether we are going on in business, law, medicine, the academy, or public service—has something we can do to help in Nepal, and in all the future Nepals we will inevitably encounter, and will (work to) repair. That is our obligation as humans and our privilege as Hoyas.

But the continued environmental change affecting the Himalayas, and indeed the world, albeit at a slower pace, is no less permanent or urgent. Much of what I found in the Himalayas – both medicinal plant species as well as the knowledge surrounding them – was disappearing even as I recorded it, or was fated soon to disappear. Conservative estimates indicate that over 35 animal and 370 plant species from the Himalayas will go extinct by 2100. And the same can be said about (environmental issues) much closer to our Hilltop. Those of you who came to us from California or are returning home there know this all too well.

Whether or not you identify yourself as an environmentalist, the environment will inevitably frame your story at (after?) Georgetown. We are at a tipping point. We will have to choose what to save and what to compromise.

We are each going to have to reevaluate our relationships with our planet. And to begin to do this, we must re-experience our environment and become aware of our ties to the natural world even as we sit here –in chairs made of ore mined from some other hilltop, surrounded by drywall made of sediment from a dry lake bed, and on top of floorboards that once supported a fruit-bearing canopy.

Our stories must respect our relationship to non-human species and our natural world because our lives and the lives of the other inhabitants of this planet depend on it. In the end, the story that we tell ourselves about the world will shape the world we inhabit.

Thank you.